The Problem with the Trolley Problem

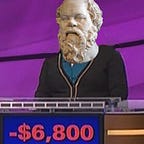

First coined and posited in 1976, the Trolley Problem has been something of a crossover smash, moving well beyond the halls of philosophy departments and into the cultural mainstream. It became a meme, served as basis for debates on self-driving cars, and even provided the topic and title of a fantastic Good Place episode. But beneath all its popularity is a critical flaw that undermines its usefulness and shows just how troubling its prevalence in our discourse should be.

The namesake problem is fairly simple — do you pull the lever and kill one person, or let the trolley roll along to kill five? Variations include pushing a man onto the track to stop the trolley, pushing the man responsible for five people being on the track onto it (termed the Fat Villain scenario), or sending the trolley off the rails and onto a man innocently minding his yard. No matter the particulars, the problem is inevitably used (when presented seriously) for a debate on utilitarianism, and the utilitarian approach of killing one to save five is the overwhelmingly popular answer.

But for this exercise to make sense, it must come with the assumption of perfect information. The operator must be certain that precisely one person will die if the lever is pulled, and that five will die if it isn’t. The assumption is one we take for granted when being posed such questions, but it severely limits — or at least, should severely limit — its relevance to the pivotal quandaries of today.

Let’s consider first the scenario posed by the trolley problem, or what it might look like more realistically. What happens when you’re the operator, and you think you might be able to save lives by pulling a lever? What if you can’t clearly see how many people are on each track? What if pulling the lever quickly carries a risk of derailment, and untold damage as a result? And what if you have too little time to calculate each possibility? How many would still act? How many would say they should?

Unfortunately, we skip over all this nuance when it comes to political questions, because our politics is loud and self-certain, and our assumption of perfect information is just as pervasive there. Our politics, in fact, are selected for this, because decisiveness is attractive in our thought leaders, and loudness and fervency tend to rise to the top in the social media age. All this is helped along by our severe ideological bubbling and the pervading confirmation bias that accompanies it. Now take into account what all these self-assured conclusions look like to those who have their own version of perfect information — essentially, like a vote to pull a lever to kill more people — and you can see just how vicious the cycle becomes.

Every tribal camp is guilty of this. When it comes to the ongoing COVID crisis in the US and Western Europe, for instance, both pro- and anti- lockdown voices seem absolutely convinced that the data are on their side, that their proposed ends are the lever pull to save lives and livelihoods. On a utilitarian basis, some solution is probably correct, but the degree of confidence is still wildly unfounded.

The issues we face are complicated. Potential solutions face unintended consequences, power vested in places where it can be abused, and logistical hurdles to enforcement and execution. To reduce them to basic questions of maths and morals is appealing, but our habitual tendency to do so is part of what is driving our discourse, and our society, so far off the rails.