Loan Forgiveness Misses the Point

Higher Education in America is more broken than we realize

Recently, Joe Biden declared loan forgiveness one of his first targets as an executive. His plan, while not without its critics, seems sensible enough — forgive up to $10,000 in debt per borrower, relieve some of the load from those who have felt overwhelmed, and maybe even add a little stimulus to a recovery-focused economy. Unfortunately, it adds up to being short-term relief for a long-term crisis, and misses the underlying problems entirely.

Our approach higher education is woefully outdated, forged by inertia and political expediency, and increasingly ill-suited to both the world of today and the world of tomorrow. What we have created is nothing less than a bubble, a self-perpetuating mass of borrowing, bureaucracy, and bloat, and simply trying to pay for the damage it has already done is not an effective solution.

Ballooning Costs, Diminishing Returns

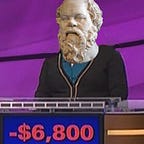

Between the 1985–1986 and the 2017–2018 school years, the average cost of attending a four-year college or university in the United States rose by nearly 500%. That sounds staggering, and it looks just as bad:

Largely to blame for these spiraling costs? Student loans, of course! With their constant subsidies, federal and state programs unnaturally bolster demand, leading prices to rise precipitously. Of course, these are programs brought into being from ostensibly the best of intentions. A college degree, after all, enables a young person to succeed in a competitive world, and will more than pay for itself, right?

It may not be so simple. On the surface, yes, an individual with a bachelor’s degree earns nearly $60,000 per year, dramatically more than the roughly $35,000 average earned by high school diploma holders, according to 2018 Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) numbers. But not every major is so lucrative — while engineering students may expect six figures by the middle of their careers, those earning degrees in social sciences, languages, and arts face far different prospects. Their earnings, it should be noted, are often unrelated to their fields of study, further diminishing the meaning of the degree — but more on that later.

Beyond the importance of major, there are quite a few confounding variables in play, largely to do with the students themselves. How many of those who earn college degrees simply have better resources growing up, better support systems, better connections, that would have put them at a money-making advantage regardless of the intermediate steps? On top of that, over the past few decades, employers have made college degrees requirements for jobs that should not logically demand them, adding an artificial value to college degrees that has little to do with anything one gets from a campus.

When all of these factors are taken into account, when one considers how increasingly easy it is to find all the information, coursework, and intellectual discussion of higher education outside of its traditional setting (a point highlighted by this year’s shift to remote learning), it begs the question — what are kids really getting out of college?

Free College Isn’t Free

If limited debt forgiveness is a fine idea that somewhat misses its mark, then free college — the cause célèbre of our progressive left — is an actively bad one. More than simply failing to root out the problem, it grows it, utterly destroying the meaning of a college degree while burdening society — degree-seekers included — with a massive cost.

The guarantee of public higher education, with the expectation that most of the population would seek it out, amounts essentially to a 16-grade public system. It is the epitome of bloat, with each level serving primarily to prepare and select students for the next, fueling the sort of dry, test-centric style of schooling that has already bred so much cynicism and disdain in our youth.

Such a push would completely erase any competitive advantage offered by a college degree, the very reason many wanted to make it more accessible. It would also dramatically increase the disadvantage held by non-degree-holders, a group that is already at a critical disadvantage. Punishing non-graduates further, when their status is so often due to environmental or economic factors beyond their control, is an impact at stark odds with the goals of greater equality and equity that drive the push for free college in the first place.

Then there is the very significant problem of cost. When Joe Biden did propose more than partial loan forgiveness, earlier in the campaign season, he estimated the cost at $750 billion over ten years — and that was his estimate. The source of these funds? Well, “by eliminating the stepped-up basis loophole and capping the itemized deductions the wealthiest Americans can take to 28%.” Even if that were enough to fund all of these lofty education plans (which other estimates have costing upwards of $1.2 trillion), it is a limited resource, one which could be utilized for far more beneficial endeavors.

And for all that money, it’s not as if it really is free for students, either. There is something called opportunity cost, after all — for many students, college means four years (sometimes five, six, or more) of being unable to engage in full-time work. It means tremendous amounts of time and energy dedicated largely to the pursuit of a nominal degree, when much of the actual learning could be done much more cheaply, and much more flexibly, online.

Correcting the Market

The political pursuit of free college for all is largely inertial — it is a simple ideal that is easy to sell, filled with buzzwords that voters and candidates love. The result, unfortunately, is a system that is antiquated, bloated, and ultimately incapable of bringing the sort of opportunity for all that its creators envisioned.

Moving beyond this, to something that makes more sense for society, begins with a more focused approach to how we support higher learning. By limiting federal aid to cases where the college education really is essential — that is, largely technical fields — we could create something that is significantly more impactful and more affordable (from the government spending standpoint) than current programs and proposals. We could really help the next generation of engineers, doctors, lawyers, teachers, nurses, and the like, helping them overcome financial hurdles in ways we could not if the aid were more generalized. This would also allow us to limit loans to cases where the receivers are most likely to be able to comfortably repay years down the line.

For everyone else (and even for those who ultimately choose to pursue technical fields), we could focus on expanding national service. By creating and supporting a variety of programs in the vein of Americorps, we could open the door to tremendous societal benefit. Not only could we give young people invaluable work experience, perspective, and fulfillment, but we could unlock a massive human resource to be leveraged for projects in counseling, mentoring, and teaching youth-in-need, in cleaning cities and roadways, in disaster response… the possibilities are limitless. This would not mean service would need to be made mandatory, simply that we would do more to emphasize it culturally and support those who choose to seek it. To the latter point, we could also provide some sort of carrot as incentive — maybe even a loan, or loan forgiveness!

By focusing less on giving degrees to as many students as possible, we can also recalibrate our broader approach to education — our problems, after all, don’t start with college. With less emphasis on high school as a means of preparing for college, we can gear our teaching less towards tests, and more towards practical skills earlier. We can focus more, at every level learning, on encouraging a sense of wonder and discovery — something far more useful in today’s world than the ability to succeed (read: get high grades and test scores) in the traditional schooling model.

And as for our colleges, we can turn them into something of an export industry. With fewer domestic students in our classrooms, international learners will be happy to fill the seats, and willing to pay for the privilege. After all, the US has a great many of the world’s top research institutions. They are a great national asset, and there is no reason we should not be earning from it.

With all of these possibilities, some loan forgiveness, in the vein of Mr. Biden’s recent declaration, may well be a logical first step. It stops some of the bleeding from our current structures, and gives us the opportunity to fundamentally shift our approach to education. But it is what we do with that opportunity that makes all the difference.